It’s a good question. The world around us, to most eyes, appears to be changing. The pervasion of digital technology is hurtling along, as a result, everything is now ‘content’ and none of us are quite sure what that means. Current affairs and events are permanently streamed at us in ways that make them seem less comprehensible than ever. Institutes, politics and even information itself are treated with suspicion and distrust. So why satire and why now?

First and foremost, the idea of there being a ‘good time’ for a satire on a challenging subject is likely a fallacy. Howe and Strauss book The Fourth Turning is among many attempting to frame the world we see before us, it’s a great book, well worth a read, yet its observation on struggle is among the most fascinating. Howe and Strauss underline that it is in times of great unrest, social friction and stress upon the population that change comes. When things are good, when people are comfortable, when it is summer and not winter – essentially, we’re all having too good a time to sign up for a challenge. It’s in the struggle and the crisis that the opportunity for change arises.

Alongside this, I was taught and have always believed that crisis often produces a high time for the arts. New Hollywood, a golden era for filmmaking in the United States, producing star after star, in classic after classic took place from the mid-1960s through till approximately 1980. This era for America as a nation was tumultuous, to say the least: the rise and end of the Civil Rights Movement, the unfolding Vietnam War, countercultural generational revolt, the Cold War, the recession, the oil crisis and Watergate. Yet through this decade and a half of revolution, changing social tides and great instability, storytelling thrived. It’s not in times of comfort that creative flair is found, it's in times of struggle and times of unrest.

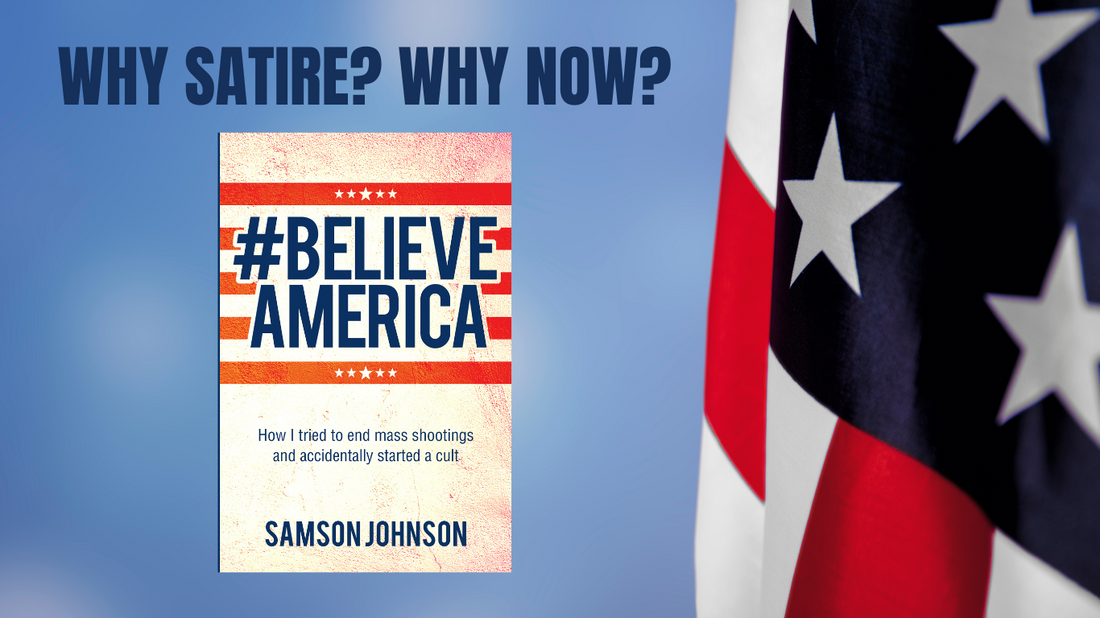

#Believe America: How I tried to end mass shootings and accidentally started a cult is following in the vein of Dr. Strangelove. There is nothing remotely funny about the threat of nuclear fallout and there certainly wasn’t at the time of its release in 1964, a high point of Cold War tensions. Conversely, there is nothing remotely funny about US gun violence and that hasn’t changed since the book’s release. In either case, humor isn’t found in the subject so much as in the relationship with it by those in power and even those elsewhere. The book spins a yarn about a thoroughly determined and engaged activist’s effort to see something done about US gun violence. Yet in Samson’s self-propelled campaign, he comes to see grander, complex realities may leave his efforts rather fated.

Writing the book took three and half to four years and it didn’t start as a book. It was a writing exercise where following the ideas was the only goal and doing so only proved them blossoming. Ultimately, the story is as much about Samson’s journey and the ideals of activism as it is to do with the subject matter. It raises questions and considerations about voice and civic participation in a time where our societal problems have never been more spelt out for us and having a platform to express has never been more accessible. The law of value is a wicked riddle; in a world where everyone has access to a voice and platform, they are less valuable than ever before. In a world where everyone can have a platform and use their voice, its value is determined by how that platform and voice are used and applied.

Samson desperately desires to do good. To see something done over a matter of life and death, a real-life transpiring problem costing several thousands of lives a year. A matter that has long been positioned as a tentpole of the culture wars. Yet like so many of us willing to throw a tweet, espouse opinion or ‘stick one’s oar in,’ how much has Samson considered what use his input is to this long-standing tragic problem? These are big mediations raising big questions. Is rampaging concern and desire to better a problem enough to make useful participation? How much does an increasingly radicalized and obstinate populous contribute to long-standing issues? How much impact can one actor have on endemic societal problems?

Bringing a reader through 60,000+ words on challenging matters requires presenting them in a digestible way. Taking the turgid and making it a page-turner. Taking that which dies in the spoken word and bringing it to life in the written word. Creativity and the arts have always been an avenue for exploring and expressing that which isn’t easily dealt with otherwise. Humor is the lungs and lifeblood of laughter, an involuntary high we are all welcome to any time we’re lucky enough to experience it. Gun violence is no laughing matter but our relationship to it: from us on the ever-divided ground, to the avoidant in positions of power, may well be laughable.

Finally, two quotes, both from much better writers than this one.

Humor is mankind’s greatest blessing.

—Mark Twain

Like a welcome summer rain, humor may suddenly cleanse and cool the earth, the air and you.

—Langston Hughes

That’s why satire, that’s why now.

_______

After several years working and writing in London, Samson Johnson now lives in a quiet corner of Scandinavia, enjoying a balcony view, a fine lady and a fur baby. That is all.