Ian Colford on the long road to publication and how The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard finally found a home 25 years after he started writing it.

I started writing the novel that became The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard in 1994. I had been writing fiction “seriously” for about a decade and had met with some success placing short stories in literary journals. I was working at the Dalhousie University Libraries and was eligible for a half-sabbatical leave. My sabbatical project was an academic paper on “digital writing.” It will seem quaint from our vantage point in the tech-saturated 2020s, but in the early 1990s widespread use of computers for writing and communication was in its infancy, and I was keen to explore the effects of the new digital tools on the act of writing.

I also had an idea for a novel and thought I could make use of the time when I wasn’t working on my official project to get started on that.

Admittedly, I was more committed to creative than academic writing. Before my sabbatical started I convinced the chair of the English Department to let me move into a vacant office. I told him that, if he had no objection, I could meet with students to discuss their own creative writing efforts. Word went out that I would be in the department for the first six months of 1994 and was available to discuss creative writing with students who found the topic of interest. I would be an informal “writer in residence.”

For the next six months, with my time and energies divided, I managed to write the first 50 pages of the novel, along with 100 pages of a text that was eventually published as a stand-alone monograph by the university.

*

Joseph had come to me fully formed: a fastidious man in his late thirties, bored with his life, who falls in love with his much younger cousin. Fiction writers know what it’s like when an imaginary character intrudes into your daily routine. Everything you do and say is coloured by a foreign perspective. Your thoughts are not entirely your own. Your observations are no longer simply things that pass before your eyes, they are potential fodder for the story you’re writing. As you work, the story becomes an obsession, and if you’re not careful it can push real life into the background. Regardless how you deal with it, you cannot help but become slightly unhinged because you’re trying to live normally under abnormal conditions.

Of course, none of this matters if the work is going well.

*

The sabbatical ended and over the next four years, while I was busy doing other things (working full time, editing a literary journal, helping to organize a reading series), I completed a first draft of the novel, which I called Sophie’s Blood. I read it over and was happy with it. And I was encouraged because I had workshopped portions of the manuscript at the Maritime Writers’ Workshop and received positive feedback.

The next step was to explore publication opportunities. It seems hard to believe now, but in 1998 large commercial publishers would take submissions straight from authors, even obscure authors like me with a sparse track record and virtually no public profile. Since there was nothing to stop me setting my sights on the biggies—Knopf, Random House, Harper Collins, M&S—I started with them.

In those days submitting a manuscript to a publisher meant printing a copy and sending it by parcel post, not an inexpensive proposition even 25 years ago. Over the next couple of years, I burned through more than a few boxes of printer paper, probably a dozen toner cartridges and hundreds of dollars in postage before deciding to take a step back to re-examine my options.

Ask anyone about the submission process and they’ll tell you many things, but they’ll tell you this for sure: it’s slow, frustrating, and the only certainty is rejection. I’ve written about this previously. Some publishers respond promptly. Others take their time. Some don’t reply at all. The level of detail in these responses varies greatly. The responses I received ranged from bluntly dismissive to gushingly complimentary. A couple of publishers apparently gave my submission serious consideration, admitting that it had come close to being accepted. One wrote back after more than a year apologizing for keeping the manuscript for such a long time, but “everyone in the office wanted to read it.”

By early 2001, however, nearly three years after finishing it, Sophie’s Blood remained unpublished. Clearly, I was doing something wrong.

(One of the many rejection letters that Colford received)

*

I reread the manuscript, which I hadn’t done in some time. Typos leapt out from almost every page. Everywhere I found clumsy syntax and passages flaunting their redundancy, begging to be cut. It was flabby and self-indulgent. I had sent the manuscript out too soon. It needed a workover. I contacted a writer friend and asked him to read it with an eye to tightening the narrative. Two or three months later I received Richard’s comments. His suggestions, if I followed through on them, would shorten the manuscript by a quarter, or about 100 pages.

I made the changes.

Now I was facing a new set of questions, the first of which was Is this manuscript really any good? It had been rejected at least 20 times. Richard had said it was okay but needed work. Well, I’d done the work.

I’m a member of the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia. I’ve served on their board, helped judge their contests. The Fed runs an annual competition for unpublished manuscripts. These days it’s known as Nova Writes. In 2001 it was called The Atlantic Writing Competition. I decided to enter Sophie’s Blood in the competition to see what would happen. One of the perks of paying the entry fee was that contestants received written comments from the jury, which was normally made up of people with a strong interest in books and storytelling: writers, librarians, booksellers, etc. I figured at the very least I’d have a few words from seasoned readers to guide my next set of revisions.

Sophie’s Blood won first prize in the novel category.

Maybe I was doing something right after all.

(Certificate from the WFNS Atlantic Writing Competition, which Colford won for The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard—then Sophie's Blood—in 2001)

*

I continued to submit the manuscript to publishers without success.

In 2003 a literary agent I was corresponding with pointed out that the movie Sophie’s Choice had made a major splash and a novel called Sophie’s World had been a global bestseller. Her point was that to avoid confusion I should either rename my character or find a better title. That’s how my novel became The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard. Years later another agent sent the manuscript to a few publishers and noticed the comments they were making often repeated a similar sentiment, that Sophie’s character was sketchy and lacked definition. She suggested I make some revisions, maybe even write a new scene or two that would help solidify Sophie in the reader’s mind. I made these changes in 2018.

By 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic was in full swing, and we were all staying home. Late in the year I suddenly found myself without an agent. I had an inventory of four unpublished manuscripts, two novels and two collections of short fiction. I reread everything, including the Confessions manuscript. It was the same narrative it had always been, the one in which Joseph Blanchard, writing in 1971, describes his role in a series of devastating, life-changing events. But while reading, I could see that the passage of almost 25 years had altered the reader’s relationship to the action. The historical perspective had shifted. The story was set fifty years in the past: a lifetime ago. It needed something to reset the balance. I hit upon the idea of a letter that would bring the novel into the contemporary moment by signalling to the reader that the story is taken from an old manuscript discovered in the home of a woman who had recently died. This letter is transcribed in the book’s the opening pages.

*

Stuck in the house and with the option of making submissions via the internet, I submitted all my manuscripts. When the rejections arrived, I submitted them again. Sometimes I didn’t even wait for the rejections to arrive. Eventually the calendar flipped to 2022 and I decided to enter The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard in the Guernica Prize competition. Here was another chance to put the work in front of readers who would not be constrained by the business side of publishing, whose chief concern was not marketing strategies or sales figures. They would simply read the novel and decide if it passed muster.

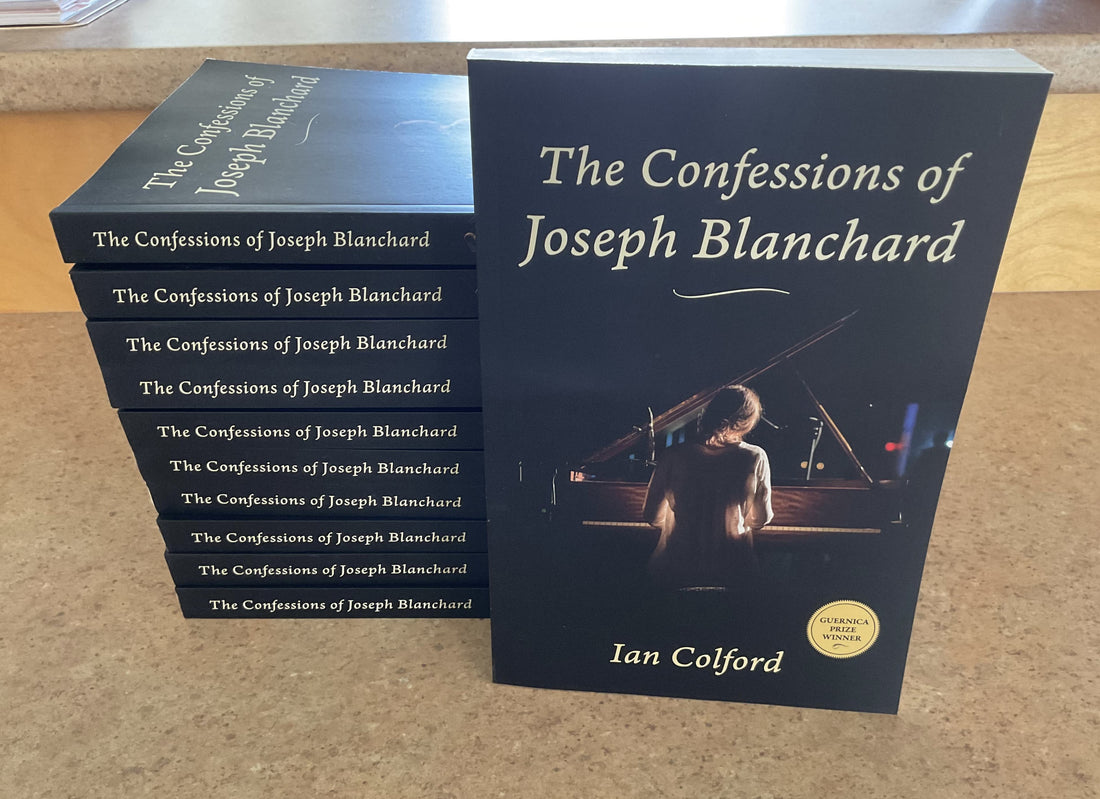

To say I was delighted to learn that The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard was selected for the Guernica Prize shortlist, and then named the winner, is an understatement. The news marked the end of a journey that was half-way through its third decade. I had long since lost count of the number of people who had read the manuscript in its various forms. But I am grateful to every one of them, especially those who went to the effort to tell me where I had gone wrong and what I could do about it. Over the years I had plenty of time to imagine what the finished product might look like, and I’m more than pleased with how it’s turned out. David Moratto’s design is outstanding, editor Lindsay Brown has done a superb job, and the whole team at Guernica Editions has been more than supportive.

I could have given up long ago, but in 1998 I believed I had written a novel that people would enjoy reading, and I still believe that. I’m glad now that readers will have a chance to decide for themselves.

(Cassidy the cat with a copy of The Confessions of Joseph Blanchard)