"Ivory Black celebrates the high romance of a certain kind of art life by putting an imaginary paintbrush into the hands of the reader and leading the way through an experience so real, it seems like more than a dream." —Nancy Robinson, award-winning surrealistic painter

One of the things that I enjoy most about being a novelist is interacting with readers at book festivals, readings, and signings and answering their questions. As my readers look at me, at this old, retired academic, holding his novel, Ivory Black, in his hands, this question sometimes comes to their minds: Why did you choose to become a writer? My answer has two parts: the fun of exploring through writing those aspects of the world that fascinate me and the need to deal with the things that haunt me.

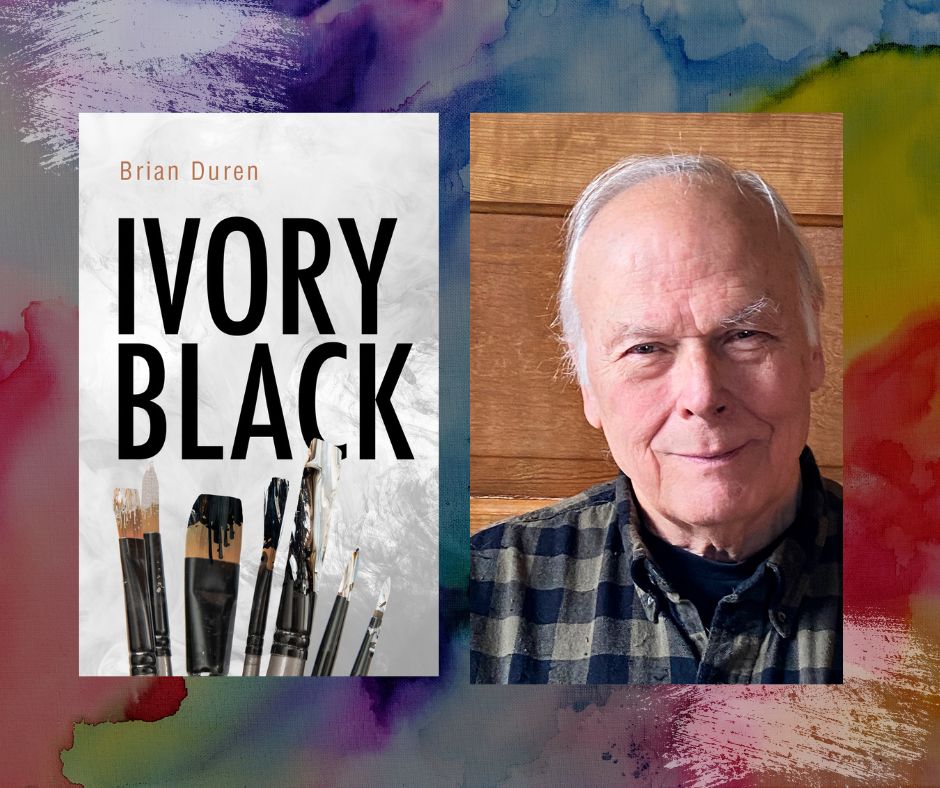

And what did I have fun exploring in Ivory Black? First and foremost, the world of the artist. I loved writing the scenes in which the main character, Dick Rayburn, learns how to draw and paint from his father, and in which Dick, as an adult, does his own paintings, and I wanted my readers to experience those scenes as if they were doing the paintings. Hence the quote from Nancy Robinson about “putting an imaginary paintbrush into the hands of the reader” and the brushes that appear on the cover.

However, I’m not an artist and didn’t grow up in a family that owned art or ever talked about it. So, how did I end up an art lover? Through love. The first love of my life was a woman whom I met at the end of my junior year in high school, the year she graduated. I was surprised to find her family had real paintings—not just reproductions—hanging on the walls in their home. She began her first year of college that fall at the Minneapolis School of Art (today, the Minneapolis College of Art and Design) and began taking me to art museums, where I would gaze at the works of Rembrandt, Vermeer, Van Gogh, Picasso, Magritte, De Chirico, Francis Bacon, Edward Hopper, and so many more painters. Our relationship ended in less than two years, but my love of art was a life-long gift from her.

When I was an undergraduate, I had to work my way through the University of Minnesota and frequently dropped out and wandered around the country, visiting major museums until, at the age of twenty-two, I bought a one-way ticket on a cargo ship and sailed from New York to South Hampton. After six weeks in England, visiting museums in London, I moved to France, fell in love with Paris, and spent most of the next ten months there, one of those months living in the bookstore, Shakespeare and Company, where homeless poets (I’d written a few poems) could stay for free. I would sometimes use my student ID for a free pass to spend the day in the Louvre, or in one of the other museums, my love for art deepening all the time. And finally, a confession: all the women with whom I’ve had amorous relationships have been artists or, in one case, an art historian.

When I set out to develop the painting style of Dick’s father, I borrowed from the work of three artists: Magritte, de Chirico, and Edward Hopper. As for Dick himself, Francis Bacon was the principal influence in my development of his style and some of his thoughts about art. But my knowledge about art that had accrued over time did not ensure that I could flawlessly describe a painter painting. I did my best, and then, after I finished the first draft of the book, and with the help of Jane Bassuk, my partner of twenty years and a painter and textile artist, I assembled a group of six painters to review the draft and point out errors. They did find a few minor details—for example, if you combine these two colors, you don’t get the color you say you do in the manuscript. But I remember, when Jane and I and the six painters sat down to discuss the draft over dinner, Nancy Robinson chose to sit next to me so she could tell me that I “really got what it is to be a painter,” and that’s what I had hoped to accomplish. I will always be thankful to this group, which included Nancy, Barbara Kreft, Joyce Lyon, Michelle Ranta, Andrée Tracy, and Lance Kiland, who died much too young.

As for the title, Ivory Black, it is the name of a fine black pigment that was used as an oil paint by many of the greatest painters, such as Rembrandt. Dick uses it to create a deep, warm, luminous darkness in the background of his paintings, a darkness inhabited by everything that haunts him. Painting, for him, is bringing what haunts him to the surface. You will have to read the book to find out what he brings to the surface and to learn about the complexity of his life. I represent that complexity by blending multiple genres and enabling Dick’s character to determine the plot.

Regarding the second part of my answer to the question, Why did you choose to become a writer, many of the things that haunt Dick haunt me as well, and writing provides me with a way of dealing with those things. For example, my problematical relationship with my father and my nomadic wanderings when I was young certainly informed Dick’s feeling, after the death of his father, of being like a planet that no longer had a sun around which to orbit; the mistakes that I made in so many of my amorous relationships and the people I hurt could be compared to Dick’s mistakes and regrets; and the unnecessary wars (the Vietnam War and the Iraq War) that killed millions of people and destroyed millions of lives and that motivated me to become an anti-war activist are certainly related to Dick’s anti-war activism. Part of Ivory Black deals with the political and corporate corruption behind the Iraq War, and the representation of that corrupt world, into which Dick is enticed, or suckered, is based on research that was motivated by my desire to reveal a resemblance of the truth through fiction.

I hope you enjoy reading Ivory Black.

Brian Duren

Brian Duren was born and raised in Minnesota. A former French professor and university administrator, he holds doctorates from the University of Paris and the University of Minnesota. After retiring from academe, Brian launched a new career as an author of literary fiction. He writes novels with an introspective quality about nomadic characters who travel through time and space, always returning to what haunts them. His first novel, Whiteout, praised by the St. Paul Pioneer Press as a “stunning debut novel, worthy of national recognition,” won the Independent Publisher Gold Medal for Midwestern Fiction. Peter Geye commented about Brian’s second book, Ivory Black, “Brian Duren is a writer of enviable talent, and Ivory Black is a novel of profound elegance,” while Junot Diaz described his third novel, The Gravity of Love, as “a magnificent haunting duet of grief, absence, and the unshakable bonds of family …” Brian is working on his fourth novel, Day Brings Back the Night. www.brianduren.com