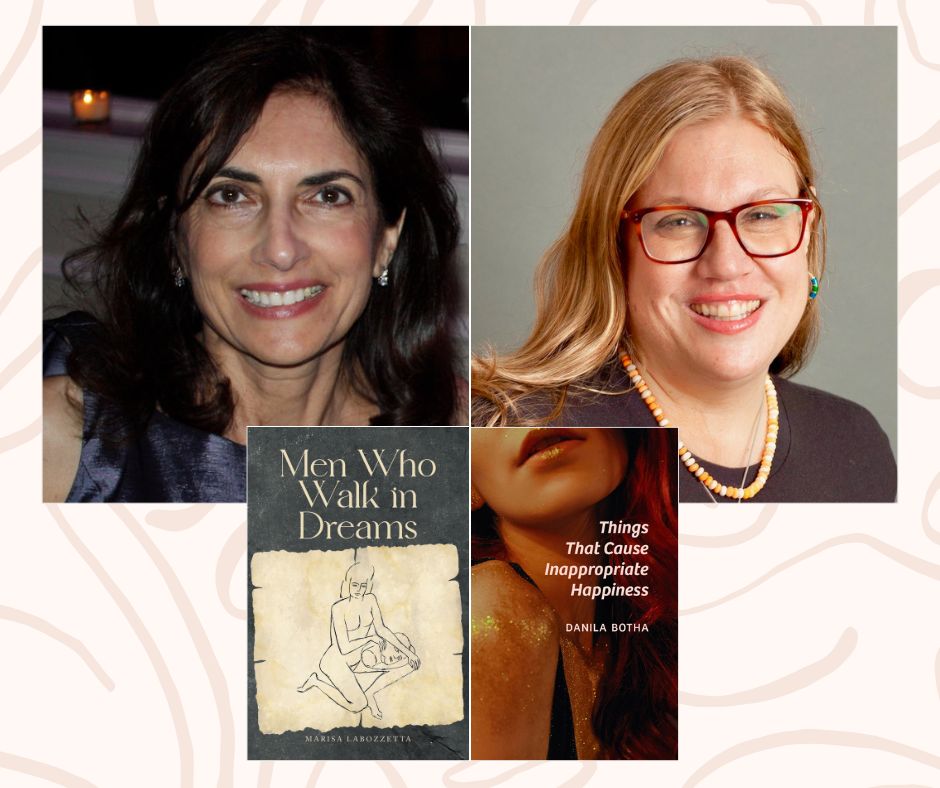

Guernica authors Danila Botha and Marisa Labozzetta dive into the short story, characterization, their influences, research for writing, and more!

Marisa Labozzetta (ML): I’m very excited to have this exchange with you because I feel we have a very similar drive of how and what we put down on paper and how we value the short story format, and how we ourselves as writers have adapted it to our own style of writing and why.

Danila Botha (DB): I feel the same way, and that’s beautifully articulated. I loved Men Who Walk In Dreams so much and I’m really excited to have this conversation with you too. Have you always felt that short fiction was your favourite medium, versus say, novel writing or anything else? I intuitively gravitated towards it when I was first studying creative writing, and my love for the economy of the form and the concision required, among other things, has only grown. What do you love most about it?

ML: I have always been drawn to short stories, whether in magazines my mother had at home, in newspapers where they occasionally appeared, or in English classes. I do not consider myself a frontrunner in the art of the long narrative. That is not to say that I haven’t enjoyed digging into the creation of a novel, but my strength is in characterization and dialogue in either form. I feel that the character is everything in my work. Once I know my character (and that is often a challenge for a while), I then know exactly how they will act and react, what they’ll wear, and what they’ll say. They become real to me. It’s amazing, but it does happen. They come from nothing, but then, as though my pages have been printed with a 3-d printer, they become their own persons. I’m also not a person who enjoys reading lengthy descriptive passages, and, yes, I love the concision demanded in a short story. Every word has to count. No that it doesn’t in a novel, but there is no leeway in short fiction. To me, the challenge is completely creating the scene and characters with a minimum of words.

DB: Your characterization and dialogue are both wonderful. It’s funny that you say that, because I feel the same way; voice and characterization are the two things that come mostly naturally to me too, and are most often my starting point in writing a story. Once I can hear their voice and I know who they are, what they like, what their backstory is, and how they’d react to any situation, then I can dive right in. I agree with you about description. To be honest, I enjoy it most when description is a facet of characterization, like a way to show the reader the unique way that this character views the world—but I also don’t love it in and of itself. I’m glad we’re on the same page about that too.

ML: What is your take on the state of the short story? Several years ago, Stephen King was editing Best Short Stories and wrote a piece in the NYTimes on how he had a hard time finding any to critique and include in that year’s anthology. He decided the state of the short story was quite dire. I can’t remember his exact words, but it was not well, let’s say.

ML: I have had books rejected because they were just that: “short stories.” Because editors tell us that no one wants to read short stories anymore. I have always disagreed with this. They began saying this just when everything in our world was being reduced to small sound bites and shorter articles. Take the revamping of the major magazine and newspapers like the NYTimes. Everyone said we don’t have the attention span we once had, and yet the short story seems to fit perfectly into this paradigm. I kept saying there will be a resurgence of the short story that publishers have killed only because they have told people they didn’t want to read them when they most likely no longer wanted to pay editors for short fiction. When I was growing up, there was a short story in every issue of almost every magazine, and before I can remember, in every newspaper.

ML: An old woman once called me some years ago to thank me for writing a collection of short stories because she could no longer read long at bedtime, but she could finish a story. I have always loved the short story form.

DB: I love that story. Short stories are perfect for a busy lifestyle. Say you have to commute every day and you have tons of time on the subway, but that’s all the time you have to read, then a short story or two is perfect. Then say there’s a period of time where you don’t have time to read. You can pick up the collection where you left off, or start anywhere, without worrying about having forgotten the key details of a novel.

DB: It's amazing to think of how ubiquitous short stories used to be. I hope we return to that. What I have noticed, as a product of our current times, is that there are far more literary journals online, from all over the world than there have ever been. I remember the days of sending a self-addressed stamped envelope in the mail, and really not being allowed to do multiple submissions. By comparison, websites like Submittable, Duosuma and Chill Subs make it so much easier in ways I wouldn’t have been able to think of.

DB: To be honest, I think there’s a lot of innovation and interesting approaches to short fiction right now. Last year, I got to sit on the jury of Danuta Gleed, which is a prize in Canada for debut short story collections. I couldn’t believe how beautiful and wildly imaginative and literary they were. There were collections that were imbued with metaphor and magic and other fantastic elements (like Paola Ferrante’s Her Body Among Animals, Rebecca Hirsh Garcia’s The Girl Who Cried Diamonds or Lindsay Wong’s Tell Me Pleasant Things About Immortality, all of which knocked me out with their brilliance), collections that were innovative with form, and subject matter (like Kathryn Mockler’s Anecdotes), and collections that were beautiful and deeply unsettling (like Lisa Alward’s Cocktail), that stayed with me, in all its wonderful details, for months.

DB: I think of how many collections I’ve deeply loved within the last few years, from Mariana Enriquez to Zoe Whittall to Heather O’Neill, to your collection, Men Who Walk In Dreams, and all the micro fiction, like Lydia Davis on and I think we’re okay. 😊

ML: Thank you for including me in that list, Danila. I’m honored! Who was your most influential short story author?

DB: Oh wow, I could go on about this for hours. I still remember where I was the first time I read an Etgar Keret story. I instantly loved his writing so much; it was so darkly funny and honest and real and wildly imaginative. I love the surreal elements and the way they were mixed so matter of factly with everyday life and vulnerabilities was so perfect. Definitely life changing for me, as was Nathan Englander.

DB: I love What They Talk About When They Talk About Anne Frank so much—the whole collection is brilliant and original and sharp and funny. From the Relief of Unbearable Urges is brilliant too.

DB: Heather O’Neill is another writer whose short fiction was just earth shattering for me. Years ago Zoe Whittall edited this incredible collection of short stories called Geeks, Misfits and Outlaws, and it featured an amazing story by her, called Seven Stops Time, and this earth shatteringly great short story by Heather O’Neill called I Know Angelo. Her imagery and metaphors were so beautiful, her descriptions were like nothing I’d ever read, and her ability to describe the complex relationship dynamic between her two characters, Chloe and Angelo, was masterful (I even named by dog Chloe after this story, that’s how much I love it. I’ve easily read a hundred times, without exaggeration). I love her collection, Daydreams of Angels, which is equally beautiful.

DB: I also love the classics, from Chekhov to Carver and Cheever. I love Chekhov’s characterization and his ability to get directly to the emotional truth. Carver’s succinctness is incredible, I don’t even know how many times I’ve read What They Talk About When They Talk about Love. Cheever is amazing in the way he takes American life and inverts it, and plays with our expectations. I love Grace Paley.

DB: I love early Margaret Atwood too. I don’t know if people know what an absolute master of short fiction she is. Every line is so well utilized, and her characterization is so sharp. Dancing Girls, Bluebeard’s Egg, Wilderness Tips, they’re all modern classics. I also love Lorrie Moore, Mary Gaitskill, and Lucia Berlin. I think everyone should read Lisa Moore’s first two short story collections, Degrees of Nakedness and Open. Michael Christie’s Beggar’s Garden was important for me too.

DB: I also love Salinger. Nine Stories, and even Franny and Zooey were huge for me as a young writer. I also love Hemingway’s short fiction. I saw a meme making fun of “Hills Like White Elephants” the other day, and I thought about subtlety and dialogue and how much it taught me. Misogyny is obviously a huge issue still, and sadly, stories about reproductive rights and what can happen if they don’t exist have never been more relevant.

DB: David Bezmosgis’s Natasha and Other Stories was life changing for me. Representation matters so much to everyone, and reading stories about the immigrant Jewish experience in Toronto, in neighborhoods I was intimately familiar with, and knowing that despite this, writing about it could be considered literary, was incredible.

DB: Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son was important for me, I had no idea that addiction could be described with so much honesty, vulnerability, and beauty, and like Carver, his style is so deliberate and succinct. Aimee Bender’s stories knock me out too. I’ve been devouring and rereading them lately: The Colour Master, The Girl with the Flammable Skirt, Willful Creatures. Her imagination is just incredible. I never feel like I’m suspending any disbelief, I’m just fully there with her, wherever she goes. Shashi Bhat’s new collection, Death By a Thousand Cuts, is incredible. So is Zoe Whittall’s new one, Wild Failure. I also loved Caroline Adderson’s A Way To Be Happy. Every single story is brilliant. Shira Nayman’s Awake in the Dark definitely influenced my most recent collection. Primo Levi too.

DB: Tell me about your influences and favourite short fiction writers and collections. I would really love to hear. Some of your stories feel so classic and literary and others feel so of moment and contemporary, and both are so beautiful. Who influenced you most?

ML: I think I began to write short stories more seriously after reading John Updike, Carver, and Cheever. I reread their collections over and over and still refer to some of the stories at times. The economy of Cheever and Carver certainly influenced me and appealed to me. But I have loved Daphne duMaurier forever and reread Don’t Look Now over and over too. Her way of telling a seemingly “normal” storyline until it isn’t normal anymore, and you have to say, “Wait a minute! What happened here?” Like Willa Cather does in “The Lottery.” When people tell me that about my stories, it makes me happy. I also love Margaret Atwood, as well as Grace Paley. I used to read a lot of Mary Gordon and Carol Shields and Nadine Gordimer’s stories and novels. I was a language major in college and grad school and so I was influenced by Gabriel Garcia Márquez’s work with regards to the “magical realism” aspect not just in his novels but in his collection of stories like Leaf Storm. I enjoy Paul Coelho’s work, but my all-time favorite is Julio Cortázar and his collection, Final del Juego, with regards to the ordinary becoming the bizarre; very Chekhovian in a way.

ML: People often ask how I decided on the order of a collection. Looking at Men Who Walk in Dreams, for example. It comes up often. Since all the stories take place in different locals and time, and the characters are not related (except for two stories) it’s almost more of a challenge to place them in order. I began with “Men Who Walk in Dreams” not just because it was the title story. In fact, at first I didn’t choose it as the opening story. But it speaks of immigration during the first great wave of immigration over a century ago, and my book ends with a story about modern day immigration. And it does happen to carry the title of the book. The last story is also a bookend of sorts to another story, “For the Love of Buffaloes,” which appears early in the collection. Sometimes the weightiness of one story might require the lightness of another to follow. Length can also be a decision maker, but less so.

DB: That’s so interesting, I was wondering that myself. I loved “For the Love of Buffaloes” so much. It moved me so deeply and I love that you came back to it. Did you ever consider opening the collection with it, or having them side by side? I love “Men Who Walk in Dreams,” it’s such a beautiful and evocative story, but that’s so interesting to hear. What was the story you chose as the title story?

ML: I did consider “For the Love of Buffaloes” as the opening story, but I preferred to keep “Sunrise,” its sequel, as the last story because, I think, all the stories jump around so much regarding place, situation, and characters, that I didn’t want to have just one storyline in succession. Also, I wanted it to be a bit of a surprise—coming back to Marguerite, who I love—and, as I said before, beginning with an immigration story of the early 20th century and ending with a modern-day one was to my liking, once I decided on the title story, “Men Who Walk in Dreams,” to be the opener.

DB: With Things that Cause Inappropriate Happiness, themes emerged that were not always planned but were exciting once I realized. I actually don’t always write with a specific collection or project in mind, I write short stories all the time. Even right now, I’m working on a new one, which weirdly, features an alligator.

DB: Even if stories seem quite different from each other, they’re often linked by theme, like a character’s identity or goals, or a period in history or even by style. In Things that Cause Inappropriate Happiness, we ended up with linking certain subjects and themes, for example, the stories set in World War II were all grouped together, and I think that worked, and there were three linked stories about the same character, which followed each other in order too.

DB: The title story was actually originally going to be the last story in the collection, “There’s Something I’ve Been Meaning to Say to You,” but an editor friend quite correctly pointed out that it sounded like the title of a few other books and collections, so I changed it to Things that Cause Inappropriate Happiness, and I’m so glad I did.

ML: I think that was a great move, and I think for your book, linking the stories with similar themes was a wise choice, since there are so many more stories in your collection than in mine.

ML: People always want to know if stories are autobiographical, or at least in some part. They are always looking for your husband or children or yourself in them. My stories are not autobiographical, and I believe yours aren’t either. Do you enjoy getting into the heads of characters as much as I do?

DB: Right, mine aren’t either. I enjoy making up stories. I enjoy researching and trying to understand how other people think and feel and why they do the things they do so much. Imagination and empathy are such a big part of the process. I really do. Do you?

ML: Yes, that’s exactly how I feel.

ML: People often ask how I can write such good dialogue. My answer is to be a good fiction writer you need three things: a good ear, a good memory, and a good imagination. That’s how you learn how people speak. Just listen.

DB: I love that. I agree. I love the way you’ve phrased that. Your dialogue is perfect by the way. I love that no matter the era, the mix of languages, or the age or background of your characters you are always able to capture the uniqueness of their voices. I always tell students to eavesdrop—listen to conversations on the subway, or in a café, and listen to how people phrase things and what that tells us about them.

ML: Where do ideas come from? That’s another question often asked. My answer is everywhere. From a statement I may have heard, to a piece of someone’s conversation somewhere when I’m sitting eavesdropping and they have no idea that I’m listening. I always tell students, don’t be so sure that the person sitting across from you is writing their grocery list. They may be jotting down pieces of your conversation. Most of it may never come to any fruition as far as my work goes, but even so, it’s the listening, the tuning in, the creation of constant curiosity that it engenders that is the greatest importance.

DB: From everywhere also. HA I love that you just mentioned eavesdropping. I can’t tell you how much that kind of thing inspires me too. Also just hearing a story that makes me think, I can’t believe that happened, and then I start imagining and wondering and there you go. I love what you said about tuning in, yes, absolutely.

DB: Do you research much for your stories? Do you enjoy that?

ML: As I say, some of my stories in this collection required a good amount of research, and others, none. Novels like Sometimes It Snows in America required a tremendous amount of research. A Day in June may have been more “familiar” to me in setting and subject matter, but it still required a lot of research. I enjoy that part of my work because I like to learn new things. I don’t like to write about the same city, the same people or population all the time, as some authors have made their hallmark doing. That’s boring to me as a writer, even though I’m sure many successful authors would say that it’s the depth of the characters and their situation that matters most, which is undeniably true. But for me, I guess it’s just part of my personality that likes to mix things up, create change regarding many things. I like to challenge myself. That’s why I write from different voices: men, women, children, priests, different ethnicities, etc.

DB: Endlessly, I love research. It’s easier than ever today to research, between YouTube and Google Maps, for example, where you can find an exact location in detail even without visiting it, and on social media you can find any image you need, you can listen to interviews or find any music, etc. I love to read about the subject, whether that’s fiction or nonfiction. I also love to talk to people who’ve lived or worked with people who know what it’s like to experience something. It’s so important to make something feel and sound authentic. I really enjoy that part of it.

DB: I have to say that the story told from the point of view of the priest, or of children, or men or women are all equally impressive. You’re so good at capturing voice and emotional depth—at making your characters feel three dimensional and human.

ML: Have you ever been criticized about writing about or in the voice of a different culture or race than your own? (I can say a lot on this).

DB: I’d love to hear your thoughts. So far, no, thankfully. I do a lot of research, I speak to people and run things by them, for example, to make sure that the language is correct, that I’m choosing the right details, that I’m being sensitive in my approach, that I’m not perpetuating anything that isn’t positive, or that is problematic, etc. I find that having people that are from that place or culture or religion reading it really helps; there’s no other way to know if you’ve gotten it right. In my novel, Too Much on the Inside, I had Brazilian friends who read Dez’s parts closely to make sure that all of those things were okay, and I had a friend from the Valley in Nova Scotia to make sure that my facts and slang were right. I’d hate for someone to read and say, “hey I’m from there, this is totally wrong,” and have it taken them out of the story. Lately I’ve been writing more Jewish characters, which doesn’t make the stories autobiographical, it just gives me a familiarity with certain subjects, but like any group, Jews aren’t a monolith, so I try to approach it from different sides too.

ML: I was criticized by some agents and editors for writing about a Somali woman, since I am not Somali or of color. At first, the book was in the first person, and so I changed it to the third to ease that situation some. I’m kind of sorry I did, however. How do we learn anything if we only write about our known kind and situations? To me, discovery is the joy and marvel of writing. If a Jewish man could write a bestseller in the voice of a Japanese woman, I didn’t understand the problem. However, I wrote the book twenty-five years ago, and maybe the attitude would be different now.

ML: I heard you comment in an interview on how you feel you can pack a lot in a very few pages of your short stories. People have commented on Men Who Walk in Dreams about how concise but also complete my writing is. Economic but elegant I think is what’s said. That in a very short number of words I can set the scene for them completely. That seems to surprise them. Again, I write that way because I like to read work like that I suppose. I like to think of myself as a cross between Cheever and Updike (not that I am on their level, but you understand!), and, as we said before, in this world, I think people appreciate that style.

DB: Economic but elegant is the perfect description, I wholeheartedly agree. I think you’re on the same level as Cheever, and Grace Paley. It’s interesting what you say about completion, that’s true. Your endings either resolve things or let us know that this is the way things are, and will be, and leave us feeling deeply for your characters as if we know them. You get to such emotional depth. I found “The Woman Who Drew on Walls” devastating in the best way, and I loved “For the Love of Buffaloes,” and “Sunrise” so much. What inspired those stories? Abandoning life to pursue the farming of buffalo mozzarella is so specific, which I love. Also, can I just say “a new silent partner, who unbeknownst to Karl had taken up residence in his pancreas…” is one of the greatest endings of a short story I’d ever read. Did you always intend for it to end that way, or did it develop as you wrote it?

ML: Thank you for the compliment. Not sure I’m on some of their levels, but certainly have aspired to get there. Your comment about the ending is exactly what my friend, the late author Mordecai Gerstein, immediately said after reading a draft of the story. I did intend on having Karl’s illness become apparent, but I didn’t know how I would do it until writing it. I felt as though I had become family with this couple and these buffaloes myself! The story was inspired when someone told me they had worked for a man who did leave his job as Karl did to make mozzarella. How can you not run with that? As for “The Woman Who Drew on Walls,” well, my mother suffered from dementia, and once, in my youth, I was trapped for a few minutes in a house with a psychiatrist who had a giant portrait in his foyer of what appeared to be a schizophrenic person. I really couldn’t say what it was supposed to be because I got out of there as quickly as I could. It’s haunted me all these years and writing about it has finally purged it from my “bad” memories.

ML: Title? People always want to know where they come from. My head has always been the answer to, “Where’s that from?” That’s not always the case with titles, for sure. Things That Cause Inappropriate Happiness is such a great title and speaks directly to just about every story. I believe that is from a source other than your head?

DB: Ha, yes. The title for Things that Cause Inappropriate Happiness came from a real side effect of the drug prednisone. It’s absolutely a work of fiction, but like the character in the story, I have rheumatoid arthritis, and I remember reading the list of side effects and thinking how bizarre that was. When I put this collection together, I started thinking about my character’s goals (sometimes they were totally inappropriate, you know?) and it felt fitting, in a greater sense for all of them.

DB: I love the title Men Who Walk in Dreams, there’s something so poetic and not quite of this world about it, and there was something about the way some of these men walked through their lives, the lack of control, the inertia, the trepidation, that feels so fitting. Did it seem that way to you too?

ML: Yes. Definitely. They are often delusional in their aspirations, misguided. They are, in some stories, also actually the men who appear in women’s dreams, for better or worse.

ML: People ask how we can write about such different types of people in my book. Do you get that? That’s why they can’t believe stories are not autobiographical. That characters can be completely constructed (Human nature is the same. Just plug in a different ethnicity, or socio-economic stance, or locale). But everyone wants to be loved and to love. To be needed and to be understood. To provide for their families. To be satisfied with their work if possible. To leave their footprint in life.

DB: I think women writers are asked that question more often than men and it’s definitely frustrating. To assume that we lack the imagination or ability to research and empathize, or that if we write women’s interior lives that the stories must be autobiographical. It came up a lot when I was touring my collection For All The Men (and Some of the Women) I’ve Known. At that point, I’d been married for a while, and had one kid already, and I thought it was more funny than anything, like, how could all these stories possibly be autobiographical, you know?

DB: I totally agree that everyone wants to be loved, and to love, to be needed and understood and satisfied. I love your phrasing here—it’s the place I approach all my characters from too.

ML: Your stories are told from the point of view of women. Is there a reason you only used women as your protagonists?

DB: That’s an interesting point that I hadn’t really thought about! I’ve definitely written from the male point of view a lot, and from lots of backgrounds. It wasn’t conscious, but I hope it feels fitting for the stories. Do you have a preference? Is there a point of view that feels easiest or most natural for you to access?

ML: Interestingly enough, I haven’t found it a problem writing from the male perspective or even from one much younger or older than myself. I may need a little fact checking at times, but for the most part, I can get into the heads of those other than a straight, white woman, and enjoy it.

ML: Quite a few of the stories relate victims with direct ties to the Holocaust or Holocaust victims. What led you to write so beautifully on that?

DB: Thank you so much. I grew up in a Jewish community where many of my friends’ relatives or grandparents, for example, were Holocaust survivors. I was interested in the sharing of stories, in things like epigenetics and intergenerational trauma, but also, in looking at what happens to people after they’ve experienced such inhumanely horrible things. What memories and habits do they hold onto vs what are they able to let go of? What effect does it have on the people around them? How do they keep living and connecting and hoping after seeing the worst of humanity? (and what if somehow, in the case of a story like “Able To Pass,” to change their family history).

DB: I was actually wondering if you drew on any family history for the title story, or what the inspiration was. It’s so beautifully written.

ML: As a child, my mother’s family used to go from Harlem in NYC to a boarding house in a place I describe for part of the summer. I remember her telling me that there was a couple in the area who had left Italy because he was a priest. There was also a story about a child who had, at one time, died because of lack of care, and I think because of the refusal of bootleggers to go for help. That was all I knew, and with that, I wove a story.

ML: Women’s struggle with their physical image is also the source of many of your characters’ efforts to bond with women they consider more desirable, and sometimes the source of their sabotaging these relationships in the process of their own self-destruction. Yet, a story like “Together We Stand” is a beautiful story about friendship. My notes say, “Down to the bare bones.”

DB: Thank you so much. That’s a really interesting observation. I have a childhood friend who recovered from cancer in our thirties. I wrote this when we didn’t know what would happen, and its fiction, but the character is very much based on her, she’s a badass. 😊

ML: “All Good Things Take Time” was probably one of the most painful stories in so many ways. Do you want to elaborate on that?

DB: Thank you for asking. Do you know what, that story was actually originally part of my novel that’s coming out this fall with Guernica, called A Place for People Like Us. In the first draft, I had alternating points of view, both Hannah’s, who is still the main character, and her best friend, Jillian. This story was originally part of Jillian’s point of view, and when I cut that out of the story, I was grateful to be able to repurpose it. It’s some of the darkest research I’ve ever done, and I’m grateful that people have received it well.

ML: The concept of what is and what appears to has always grabbed me, and I feel that is at the root of many of your characters’ perception of situations.

DB: That’s such an interesting insight, totally. It’s always grabbed me too, and I can see it in your stories as well.

DB: One last question for you: What are you working on these days? Do you write short stories often, all the time, or only when you’re working on a specific project?

ML: I have gone from writing short stories as separate entities (even those that were later put into the collection At the Copa) to working towards a collection, like Thieves Never Steal in the Rain, where each story can stand alone. However, this book about five Italian American female cousins in America and at times in Italy, reads like a novel, in the way Joan Silber’s The Size of the World does (though it’s labeled as a novel, it appears to be a collection of short stories, at least to me). Clearly, the stories in Thieves Never Steal in the Rain were written with the intention to be one book, as were the stories in Men Who Walk in Dreams. While I started out with one or two stories in both of those collections, I quickly realized I was on to something bigger, and worked toward that goal, albeit a different goal than in Thieves Never Steal in the Rain. And right now I’m back to writing stories that, so far, are not related, but that can always change. J

ML: Thank you so much, Danila, for this informative and enjoyable dialogue we’ve been able to have. I can’t wait to read your next book!

DB: Thank you so much, Marisa. I can’t wait to read yours!